The Story of Ultimaker: 3D Printers with Open Source DNA

Paul CroftFor those who have been immersed in a capitalist society, open source thinking can seem counterintuitive. For the last three decades wealth has been determined through ownership and property rights. Businesses have been valued and financed based on the patents they own and the applications of their intellectual property. But open source, a term originating from software code being open for other developers to use, has started to change the prevailing capitalist mentality. Innovation is essential to their survival, and companies are seeing open source thinking, like sharing and collaborating, as a methods towards that goal.

Paul CroftFor those who have been immersed in a capitalist society, open source thinking can seem counterintuitive. For the last three decades wealth has been determined through ownership and property rights. Businesses have been valued and financed based on the patents they own and the applications of their intellectual property. But open source, a term originating from software code being open for other developers to use, has started to change the prevailing capitalist mentality. Innovation is essential to their survival, and companies are seeing open source thinking, like sharing and collaborating, as a methods towards that goal.

Open source thinking can also be applied to the business of hardware development. But, is it sustainable? How can we invest in new startups that intend to bring products to market if competitors can just use or copy their work? Why would customers buy products if there isn't a trademarked brand behind it? How will litigation be used to protect the offering if there's no patents in place? How will we make money from this hardware product?

Today we're seeing open hardware projects and businesses succeed for the first time in history. Why, and what do they look like? The story of the Ultimaker and its user community proves that being open is in fact sustainable and may even go a step further to say that that sharing and collaboration are genuine routes to innovation.

Image by Opensource.com

Image by Opensource.comLet's go back several years to a makerspace in Utrecht, a big city in the Netherlands. The founders of Ultimaker, a premium 3D printer manufacturer, were inspired by the potential of 3D printing, and experimenting with the open source designs of the RepRap project. The project was initiated by Dr. Adrian Bowyer (of the University of Bath) who wanted to create a low-cost 3D printer that could print most of its own components. That, combined with making the design files accessible online to anyone, meant there were almost no barriers to building your own 3D printer.

"Ultimaker is committed to sharing new designs, functions and updates with our customers to give them the freedom to 3D print to the best of their ability. Being open source enables quick iterations and innovation which pushes the boundaries of the impossible every time. It means our innovations are community-powered and the focus lies not only on what we think is important, but also allow our users to grow and transform with us as we develop new technology," says Siert Wijnia, founder of Ultimaker.

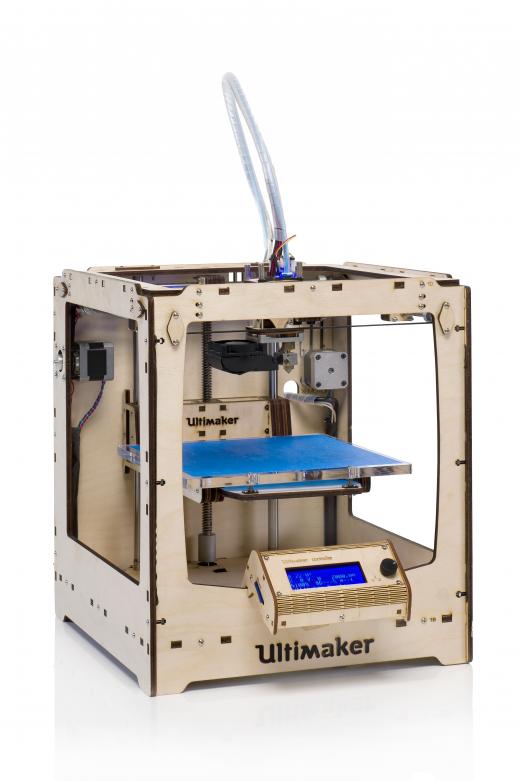

Ultimaker original, 3D printer (CC BY-SA 4)

Ultimaker original, 3D printer (CC BY-SA 4)The Ultimaker Original was hugely popular, initially only avaliable as a kit. The kit included all of the components needed to assemble your own 3D printer: from laser cut panels to stepper motors and circuit boards. The Ultimaker kit borrowed elements of the RepRap project while focusing more on speed and quality rather than self replication. From the start, the founders viewed their customers as part of the Ultimaker community. Rather than simply bringing a hardware product to market and creating the next version of it internally, they shared the design files openly and listened to the feedback of their customer community.

To encourage more and better feedback, the founders established online community forums and participated in maker events with collaborators across Europe. They met and embraced like-minded people who shared their vision for open innovation and wanted to improve the product.

One such Ultimaker user is Anders Olsson, a research engineer working on neutron particle experiments. Due to the dangerous nature of dealing with neutrons, he had to use boron carbide in his experiments that required that he craft physical objects. But boron carbide is an extremely hard ceramic material, used for tanks and bulletproof vests, so many researchers opt to use toxic alternatives like cadmium instead.

Anders tried something different. He added the boron carbide to his Ultimaker to craft objects, and it worked!

Eventually, the standard brass nozzle on the Ultimaker became damaged due to the hardness of boron carbide, and at the time changing the nozzle meant replacing the entire heater block. But because Ultimaker is open, Anders was able to solve his problem: he designed a heater block with a threaded screw that would allow him to change a nozzle. It was up and operating flawlessly in no time.

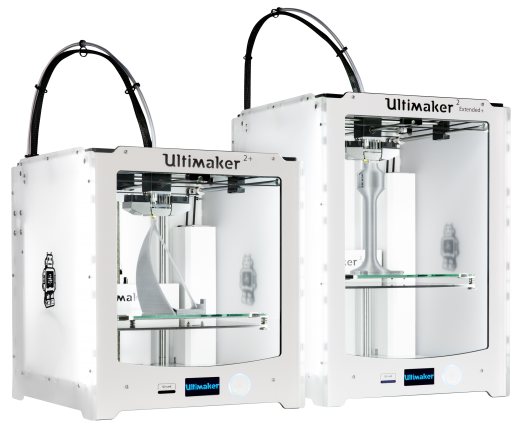

Ultimaker 2+ printer (CC BY-SA 4)

Ultimaker 2+ printer (CC BY-SA 4)Then, Anders shared his solution on the community forum. Fellow Ultimaker users didn't need to create objects with boron carbide, but the innovation of changing the nozzle diameter allowed more detailed and faster printing, and it allowed users to print with different materials. The Olsson Block, as it was named, was given away free with every printer at the end of 2015 and the founders incorporated it into the design of the next version: the Ultimaker2+ family.

Today, Ultimaker continues be guided by open source thinking. We strive to share our knowledge and that of the community with others, and to connect people within their communities. This ethos continues to propel Ultimaker to the forefront of the emerging 3D printing field and opens up new opportunities for others. Ultimaker printers are now used for amazing open hardware projects like those of the award winning Wevolver project and to support life changing initiatives like the e-NABLE project.

| The story of Ultimaker: 3D printers with open source DNA was authored by Alex Paul Croft and published in Opensource.com. It is being republished by Open Health News under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0). The original copy of the article can be found here. |

- Tags:

- 3D printer manufacturer

- 3D printers

- 3D printing

- Adrian Bowyer

- Anders Olsson

- boron carbide

- carving physical objects

- ceramic materials

- community-powered innovations

- e-NABLE project

- hardware development

- intellectual property

- life changing initiatives

- maker events

- Netherlands

- neutron particle experiments

- Olsson Block

- Open Hardware

- open hardware projects

- open source

- open source designs

- open source hardware

- open source thinking

- Paul Croft

- RepRap project

- Siert Wijnia

- Ultimaker

- Ultimaker kit

- Ultimaker2+ family

- University of Bath

- Utrecht

- Wevolver project

- Login to post comments