The Shutdown Will Harm the Health and Safety of Americans, even After it's Long Over

Morten WendelboWith the U.S. federal government shutdown now the longest in history, it's important to understand what a shutdown means for the health and safety of Americans.

Morten WendelboWith the U.S. federal government shutdown now the longest in history, it's important to understand what a shutdown means for the health and safety of Americans.

The good news is that in the short run, the consequences are relatively few. But, as a researcher who studies natural disaster planning, I believe that Americans should be worried about the federal government's long-term ability to ensure good public health and protect the public from disasters.

As the shutdown drags on, it increasingly weakens the government's ability to protect Americans down the road, long after federal workers are allowed to go back to work. Many of these effects are largely invisible and may feel intangible because they don't currently affect specific individuals.

However, the shutdown poses a very real threat to preparedness for future emergencies, such as natural disasters and disease outbreaks. It also damages the government's ability to recruit and retain the experts needed to work at the cutting edge of public health.

Disaster preparedness and response

Much funding for disaster recovery that is already underway is funded in appropriations separate from those that fund the shuttered parts of government.

On Dec. 26, however, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which contracts private contractors for a large share of their work, ordered its contractors to cease working on several projects. Even for programs with funding, progress is made difficult by a shortage of several thousand staff members.

When President Trump signaled to the Senate that he would not sign into law the appropriations bills that had passed the House, leading to the shutdown, funding with bipartisan support for disaster recovery died too. This impedes disaster relief efforts in the states that experienced a disaster in the past two years. Among others, it leaves victims of the forest fires in California and victims of Hurricane Florence in the Carolinas waiting for crucial help needed to recover.

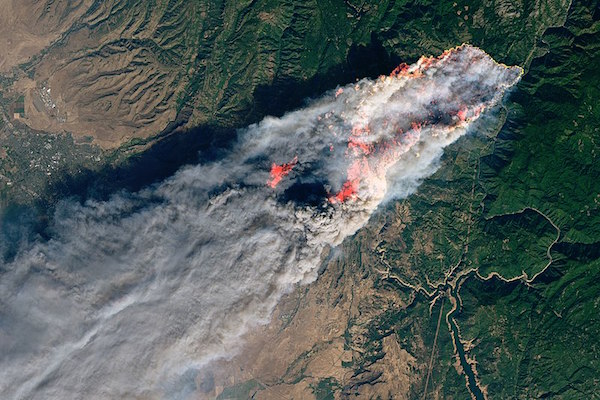

NASA Landsat 8 Image of Camp Fire

NASA Landsat 8 Image of Camp Fire

The shutdown also weakens the government's ability to foresee, prevent and respond to upcoming natural disasters. For example, hurricane modelers with NOAA, the agency chiefly responsible for storm forecasts, are furloughed.

In California, dozens of people recently died in the worst forest fire in the state's history, while more than 10,000 homes were destroyed. These forest fires were so severe in part due to how forests have been managed. However, more than half of all of California's forests are managed by the federal government. During the shutdown, those forests are not being managed at all.

In general, first responders and emergency experts use the offseason to prepare for the next disaster season, but reports show that the prolonged shutdown is preventing some of this preparation, such as training for essential staff and forecasters.

More scary still is the possibility of a widespread disease. The lapse in funding also means that the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act did not renew as expected. This act lets the federal government fund the development of emergency medicine, as well as new medications in advance of future outbreaks, among many other disaster preparedness functions it funds. Even with a fully functioning federal government, several critical supply chains broke down during last year's flu season, preventing delivery of basic medical goods like saline.

The shutdown severely weakens the ability of the federal government to respond to new threats, even after the shutdown has ended.

Losing dedicated public servants in public health

After the shutdown is over, it will probably also prove difficult for the U.S. to retain some of the staff who are crucial to the success of public health - even more so than in most other sectors of the federal government which will also struggle to retain its public servants.

Roughly half of the staff at the Department of Health and Human Services are deemed essential and continue to work despite the shutdown. The other half has been sent home. But neither group is getting paid.

President Donald J. Trump, is joined by California Governor Jerry Brown, Governor-elect Gavin Newsom, FEMA Administrator Brock Long and Paradise, Calif., Mayor Jody Jones, as he survey's the fire damage to Skyway Villa Mobile Home and RV Park Saturday, Nov. 17, 2018, in Paradise, Calif., which was devastated by the Camp fire. Credit Shealah CraigheadDuring brief shutdowns, many of which have historically lasted only one to three days, such a lapse in pay is frustrating, but typically a surmountable challenge for most federal workers. During a shutdown lasting weeks, with no end in sight, it means hundreds of thousands of families struggle to pay for rent, school fees, medical care and other expenses essential for their own safety and well-being.

President Donald J. Trump, is joined by California Governor Jerry Brown, Governor-elect Gavin Newsom, FEMA Administrator Brock Long and Paradise, Calif., Mayor Jody Jones, as he survey's the fire damage to Skyway Villa Mobile Home and RV Park Saturday, Nov. 17, 2018, in Paradise, Calif., which was devastated by the Camp fire. Credit Shealah CraigheadDuring brief shutdowns, many of which have historically lasted only one to three days, such a lapse in pay is frustrating, but typically a surmountable challenge for most federal workers. During a shutdown lasting weeks, with no end in sight, it means hundreds of thousands of families struggle to pay for rent, school fees, medical care and other expenses essential for their own safety and well-being.

For many personal contractors, who make up hundreds of thousands of the federal government workforce, the loss of pay may be permanent.

This will all make it substantially less attractive to be a federal worker in the future. That is especially true for workers in public health. Although federal jobs often pay as well or even better than the private sector, that is not true for the field of public health, where workers often take pay cuts to become public servants.

To make matters worse, the president has signaled that federal salaries will be cut for 2019. Together, the pay cut and the shutdown may push government employees to join the private sector, leaving the federal government less capable of taking on public health challenges and disasters in the future.

Morten Wendelbo, Research Fellow, American University School of Public Affairs

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Tags:

- Brock Long

- Camp Fire

- Disaster Preparedness

- disaster recovery

- disease outbreaks

- Donald J. Trump

- emergency experts

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

- Federal Government

- first responders

- forest fires in California

- Gavin Newsom

- government shutdown

- health and safety of Americans

- Hurricane Florence

- Jerry Brown

- Jody Jones

- man-made disasters

- Morten Wendelbo

- NASA Landsat 8

- natural disaster planning

- natural disasters

- Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA)

- preparedness for future emergencies

- public health

- The Conversation

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

- Login to post comments