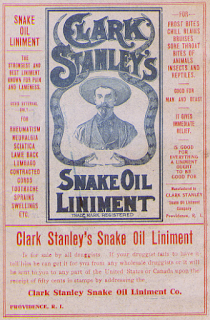

Kim BellardThe head of the AMA -- James Madara -- got a lot of headlines with his speech at the AMA annual meeting last weekend that, among other things, warned of the "digital snake oil of the early 21st century." Dr. Madara included in this category "from ineffective electronic health records, to an explosion of direct-to-consumer digital health products, to apps of mixed quality.

Kim BellardThe head of the AMA -- James Madara -- got a lot of headlines with his speech at the AMA annual meeting last weekend that, among other things, warned of the "digital snake oil of the early 21st century." Dr. Madara included in this category "from ineffective electronic health records, to an explosion of direct-to-consumer digital health products, to apps of mixed quality.

Dr. Madara is frustrated with products that make care less efficient -- he cited an AMA study that found 50% of physician's time was spent on a keyboard, making them "the most expensive data entry workforce on the face of the planet" -- while interfering with the patient-physician relationship, and many of which have no proof of efficacy.

Not surprisingly, he scorns the DIY health movement.

But, not to worry. Dr. Madara promised that physicians will be involved in future generations of such digital products, rather than their being developed "flying on an entrepreneur's incomplete views." He seems to believe that digital health vendors have neither consulted with physicians nor have any on their teams. He also ignores the fact that health care providers have allowed the federal government to pay out some $33b in our tax dollars on those digital snake oil EHRs for them, rather than holding out on principle for better products.

A different take on "snake oil" in health care was a thoughtful piece in Health Affairs, by David Newman and Amanda Frost, discussing the quality measurement morass in health care. They cite a study that estimated we spend some $15.4b annually collecting several thousand different quality measures, few of which have any meaning to consumers and all-too-few of which seem to be used to actively improve quality.

It isn't that they don't think we should be measuring quality -- far from it -- but, rather: "Patients should not be able to choose substandard quality care, and substandard quality care should not be allowed to be offered in the market."

Now, there's a novel concept! They noted that you can't eat at restaurants that fail their health inspection, even if they were to offer lower prices to compensate for the lower quality. They're closed until the identified issues are addressed. Yet you can get care from providers who are known, objectively or subjectively, to be delivering substandard care. And, oh, by the way, the people overseeing who is allowed to keep delivering care are other physicians; it is as if the restaurant association was responsible for those restaurant health inspections.

They noted that you can't eat at restaurants that fail their health inspection, even if they were to offer lower prices to compensate for the lower quality. They're closed until the identified issues are addressed. Yet you can get care from providers who are known, objectively or subjectively, to be delivering substandard care. And, oh, by the way, the people overseeing who is allowed to keep delivering care are other physicians; it is as if the restaurant association was responsible for those restaurant health inspections.

Dr. Newman and Dr. Frost want to hold providers, payors, managers, professional associations, and regulators responsible for demanding quality improvement, rather than throwing a bunch of quality metrics at consumers in hopes that they will sort it out somehow.

That's the kind of snake oil that the AMA should be targeting.

It's not just poor quality care. It's also care of questionable -- or even no -- value. Stat News just published an article profiling a tool that most consumers, and probably many physicians, have never heard of. It's called "number needed to treat," or NNT. It is a calculation that quantifies how many people would need to get a given therapy in order for one person to benefit from it. You'd think that number would be close to one, but it rarely is.

For example, seven post-surgical patients have to wear compression stockings to save one from developing deep-vein thrombosis (blood clots). Moreover, the downside risks of wearing them are minimal, so having them as a common practice makes sense. On the other hand, 104 healthy people would have to take statins for five years in order to save one from a heart attack. Almost 1,700 healthy people need to take aspirin every day for a year to prevent one heart attack or stroke.

Those are not such great odds of success.

Experts suggest that NNTs of 5 or less are associated with a meaningful health benefit, and over 15 probably at best only a small one. The amazing thing is how many therapies have high NNTs. The NNT website rates therapies into four categories:

- Green: clear health benefits that outweigh any associated harms. Example -- antibiotics for open fractures.

- Yellow: the data are not clear about benefits/risks and require more study. Example -- antibiotics for sinusitis.

- Red: Benefits and harms are about equal. Example -- antibiotics for acute bronchitis.

- Black: "Very clear" associated harms without any recognizable benefit. Example -- PSA test for prostate cancer.

NNT also reviews diagnostic evaluations, providing a color-coded summary of how helpful they are for the particular disease conditions. Again, there are extremely wide variations.

The question is twofold: one, why are so many of the therapies with red or even black ratings still performed, and, two, why isn't the NNT always part of the conversation with the patient? For that matter, why isn't the NNT available for more therapies?

Yes, certainly EHRs should be better. Yes, direct-to-consumer digital health products and apps should be thoroughly (and transparently) evaluated. Yes, physician offices should be part of the digital data ecosystem surrounding each person, taking advantage of, and contributing to, data about that person and the broader population. And, no, data entry is not what we want our health care providers spending the majority of their time on.

But all that is the tail wagging the dog. In the early 21st century, we should have better data on the effectiveness and risks of what is being done to patients. That data should be available to guide physician recommendations and patients' informed consent about their care. Those are the discussions we deserve to be having.

If we're making decisions in the absence of such data -- or despite it -- then we're back to the "snake oil" days Dr. Madara proudly claims the AMA took care of over a hundred years ago. This time, though, they're the ones selling it.

If we're going to be talking about "snake oil" in health care, there may be better targets than apps.